by

The recent Surgeon General’s “Call to Action to Implement the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention” highlighted suicides as a significant public health problem. In 2019, there were 47,500 suicide fatalities in the U.S. and an estimated 1.4 million suicide attempts[1].

The causes of suicide are complex, with many personal, socio-demographic, medical, and economic factors playing a role. One potential risk factor is occupation and several occupations appear to be at higher risk for suicide, including first responders[2].

First responders, including law enforcement officers, firefighters, emergency medical services (EMS) clinicians, and public safety telecommunicators, are crucial to ensuring public safety and health.

First responders may be at elevated risk for suicide because of the environments in which they work, their culture, and stress, both occupational and personal.

This stress can be acute (associated with a specific incident) or chronic (an accumulation of day-to-day stress). Occupational stress in first responders is associated with an increased risk of mental health issues, including hopelessness, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, as well as suicidal behaviors such as suicidal ideation (thinking about or planning suicide) and attempts[3].

Even during routine shifts, first responders can experience stress due to the uncertainty in each situation. During emergencies, disasters, pandemics, and other crises, stress among first responders can be magnified.

Relationship problems have also been linked to a large proportion of suicides among the general population (42%)[4]. Because first responders can have challenging work schedules and extreme family-work demands, stress caused by relationship problems may also be magnified in this worker group.

Law enforcement officers and firefighters are more likely to die by suicide than in the line of duty[5]. Furthermore, EMS providers are 1.39 times more likely to die by suicide than the public [6].

Studies have found that between 17% and 24% of public safety telecommunicators have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 24% have symptoms of depression [7].

While telecommunicators are often the very first responders engaged with those on the scene, research on their suicide risk and mental health has lagged.

Even given the high number of suicides, these deaths among first responders are likely underreported. There are insufficient data on suicides and mental health issues among these workers.

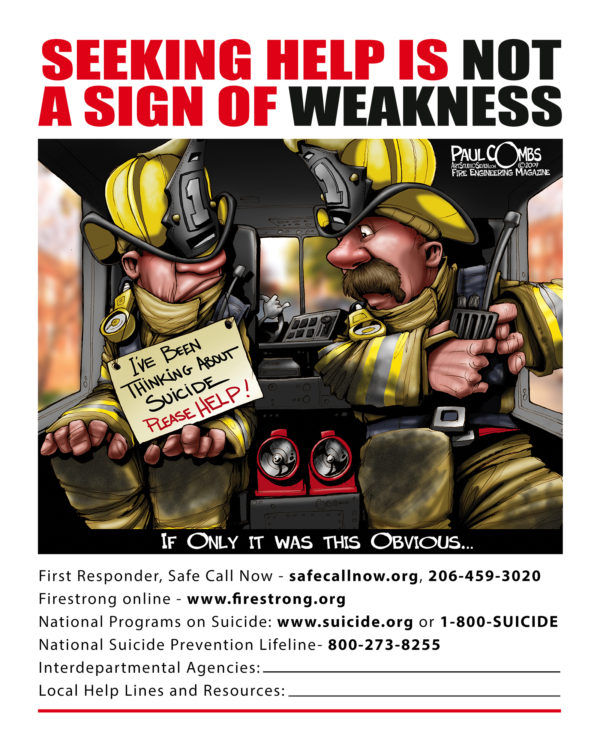

Many first responders may consider stress to be ‘part of the job’ and feel that they cannot or should not talk about traumatic events and other occupational stressors.

The perceived stigma around mental health problems or concerns over the impact on employment (i.e. being labeled “unfit” for duty) may lead first responders to not report suicidal thoughts.

Additionally, occupational data may be incomplete or difficult to capture for first responders, who often have multiple jobs and/or work in a volunteer capacity.

More complete data are needed to identify risk and protective factors and to design evidence-based suicide prevention programs for first responders. In addition, prevention programs should reflect the differences among first responder groups and be tailored to each worker population.

What Is Being Done to Prevent Suicides Among First Responders

There are several research activities to better understand and prevent suicides among first responders.

As a first step, an inter-agency team of researchers from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is analyzing suicides among first responders using the most recent three years of National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) data available.

The NVDRS is the only state-based surveillance system that collects data on all types of violent deaths – including homicides and suicides. This analysis will describe the circumstances of suicides among first responders.

While current NVDRS data can provide a basic understanding of first responder suicides, there are many missing data elements still needed to complete our understanding of these suicides.

To address this gap in data, in 2020 the U.S. House and Senate approved funding for the Helping Emergency Responders Overcome (HERO) Act.

This legislation directs the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to create a Public Safety Officer Suicide Reporting System to increase our knowledge of these events.

The module will build upon elements collected as part of the current NVDRS infrastructure from the required source documents (death certificates, coroner/medical examiner reports, law enforcement reports) and will include information specific to the first responder community. These data will provide opportunities to better understand suicide fatalities and the circumstances around those fatalities among first responders.

Challenges and Successes

While enhancing data collection is an important step, we must recognize that many challenges are present for suicide prevention within these occupations. For example, there are few evidence-based interventions for first responders.

Over the years there has been increased demand for interventions, yet most that are currently available have not been thoroughly evaluated.

The military has conducted extensive resilience training and many first responder organizations are adapting this type of training for their populations, but without data, it is difficult to evaluate its impact.

Another challenge is the limited culturally competent mental health resources for first responder’s mental health needs. Often, first responders are sent to general mental health practitioners who may not understand the unique demands faced by first responders or the cultures in which they operate.

While they may meet the needs of many clients, general practitioners may not understand what first responders experience on the job or be able to relate to them in a culturally competent manner.

For many first responders, the transition from being a provider to a client or patient is not an easy one. When a first responder finally seeks treatment, it can be devastating to encounter an ill-prepared provider and may result in a reluctance to seek further help.

It is also important to highlight effective approaches to improving first responders’ mental health while noting that data on the effectiveness of these approaches with first responder groups is limited. One successful approach has been the use of peer-to-peer counseling and peer teams. Sometimes having peers who model healthy behaviors can assist in linking first responders in need of support to additional resources.

Another successful approach has been the use of formal and informal post-event decompression sessions. These meetings are sometimes called a hot wash, debrief, or lessons learned.

Building a routine practice to discuss what went well, how the response could have been improved, and any other issues after each call can also set the stage for these discussions to become routine and provide opportunities for responder decompression.

While more casual meetings are not the same as more formal Critical Incident Stress Debriefings or post-event decompressions, any type of post-event debrief could help normalize discussions about mental health and suicide within first responder groups.

If you or anyone you know needs help, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255). This is free and confidential. You will be connected to a counselor in your area. For more information, visit the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline website.

Hope M. Tiesman, PhD, is a research epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Katherine L. Elkins, MPH, is an EMS/911 Specialist in the NHTSA Office of Emergency Medical Services.

Melissa Brown, DrPH, is a Behavioral Scientist in the NCIPC Division of Injury Prevention.

Suzanne Marsh, MPA, is a Team Lead in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Leslie M. Carson, MPH, MSW, is a highway safety specialist in the NHTSA Office of Impaired Driving and Occupant Protection.

References

[1] Stone DM, Jones CM, Mack KA. Changes in Suicide Rates — United States, 2018–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:261–268

[2] (SAMHSA. May 2018. Disaster Technical Assistance Center Supplemental Research Bulletin First Responders: Behavioral Health Concerns, Emergency Response, and Trauma)

[3] SAMHSA. May 2018. Disaster Technical Assistance Center Supplemental Research Bulletin First Responders: Behavioral Health Concerns, Emergency Response, and Trauma.)

[4] Petrosky E, Ertl A, Sheats KJ, Wilson R, Betz CJ, Blair JM. Surveillance for Violent Deaths — National Violent Death Reporting System, 34 States, Four California Counties, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ 2020;69(No. SS-8):1–37

[5] https://rudermanfoundation.org/white_papers/police-officers-and-firefighters-are-more-likely-to-die-by-suicide-than-in-line-of-duty/.

[6] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10903127.2018.1514090

[7] Lilly, MM & Pierce, H. 2013. PTSD and depressive symptoms in 911 telecommunicators: the role of peritraumatic distress and world assumptions in predicting risk. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(2):135-41)

Posted on by

more recommended stories

Fentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to Spike, Making San Diego a National Epicenter for Fentanyl Trafficking

Fentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to Spike, Making San Diego a National Epicenter for Fentanyl TraffickingFentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to.

Utah Man Sentenced for Hate Crime Attack of Three Men

Utah Man Sentenced for Hate Crime Attack of Three MenTuesday, August 8, 2023 A.

Green Energy Company Biden Hosted At White House Files For Bankruptcy

Green Energy Company Biden Hosted At White House Files For BankruptcyAug 7 (Reuters) – Electric-vehicle parts.

Former ABC News Reporter Who “Debunked” Pizzagate Pleads Guilty of Possessing Child pδrn

Former ABC News Reporter Who “Debunked” Pizzagate Pleads Guilty of Possessing Child pδrnFriday, July 21, 2023 A former.

Six Harvard Medical School and an Arkansas mortuary Charged With Trafficking In Stolen Human Remains

Six Harvard Medical School and an Arkansas mortuary Charged With Trafficking In Stolen Human RemainsSCRANTON – The United States.

Over 300 People Facing Federal Charges For Crimes Committed During Nationwide Demonstrations

Over 300 People Facing Federal Charges For Crimes Committed During Nationwide DemonstrationsThe Department of Justice announced that.