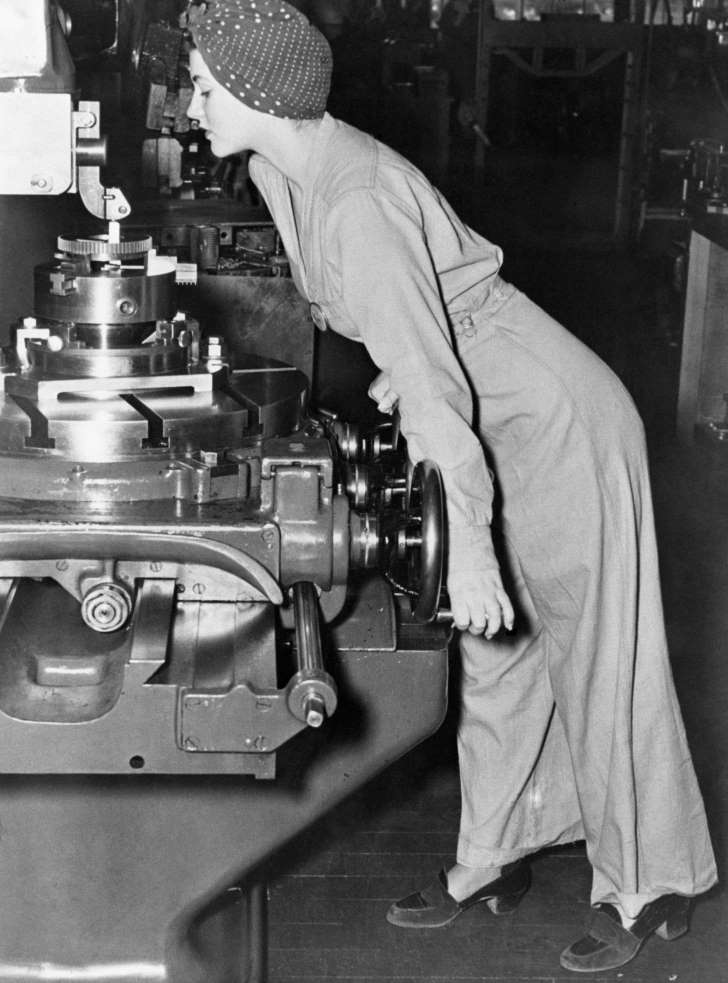

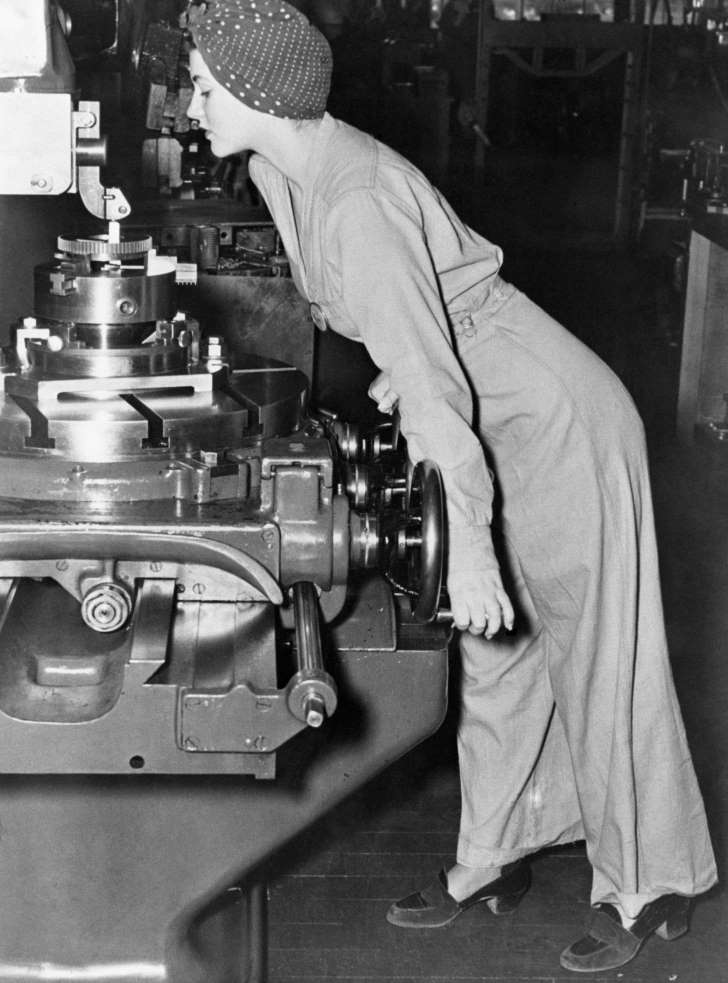

© Getty Images A 1942 photograph of Mrs. Fraley that was the likely inspiration for the Rosie the Riveter poster.

Unsung for seven decades, the real Rosie the Riveter was a California waitress named Naomi Parker Fraley.

Over the years, a welter of American women have been identified as the model for Rosie, the war worker of 1940s popular culture who became a feminist touchstone in the late 20th century.

Mrs. Fraley, who died on Saturday, at 96, in Longview, Wash., staked the most legitimate claim of all. But because her claim was eclipsed by another woman’s, she went unrecognized for more than 70 years.

“I didn’t want fame or fortune,” Mrs. Fraley told People magazine in 2016, when her connection to Rosie first became public. “But I did want my own identity.”

The search for the real Rosie is the story of one scholar’s six-year intellectual treasure hunt. It is also the story of the construction — and deconstruction — of an American legend.

“It turns out that almost everything we think about Rosie the Riveter is wrong,” that scholar, James J. Kimble, told The Omaha World-Herald in 2016. “Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.”

For Dr. Kimble, the quest for Rosie, which began in earnest in 2010, “became an obsession,” as he explained in an interview for this obituary in 2016.

His research ultimately homed in on Mrs. Fraley, who had worked in a Navy machine shop during World War II. It also ruled out the best-known incumbent, Geraldine Hoff Doyle, a Michigan woman whose innocent assertion that she was Rosie was long accepted.

On Mrs. Doyle’s death in 2010, her claim was promulgated further through obituaries, including one in The New York Times.

Dr. Kimble, an associate professor of communication and the arts at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, reported his findings in “Rosie’s Secret Identity,” a 2016 article in the journal Rhetoric & Public Affairs.

The article brought journalists to Mrs. Fraley’s door at long last.

“The women of this country these days need some icons,” Mrs. Fraley said in the People magazine interview. “If they think I’m one, I’m happy.”

The confusion over Rosie’s identity stems partly from the fact that the name Rosie the Riveter has been applied to more than one cultural artifact.

The first was a wartime song of that name, by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. It told of a munitions worker who “keeps a sharp lookout for sabotage / Sitting up there on the fuselage.” Recorded by the bandleader Kay Kyser and others, it became a hit.

The “Rosie” behind that song is well known: Rosalind P. Walter, a Long Island woman who was a riveter on Corsair fighter planes and is now a philanthropist, most notably a benefactor of public television.

Another Rosie sprang from Norman Rockwell, whose Saturday Evening Post cover of May 29, 1943, depicts a muscular woman in overalls (the name Rosie can be seen on her lunchbox), with a rivet gun on her lap and “Mein Kampf” crushed gleefully underfoot.

Rockwell’s model is known to have been a Vermont woman, Mary Doyle Keefe, who died in 2015.

But in between those two Rosies lay the object of contention: a wartime industrial poster displayed briefly in Westinghouse Electric Corporation plants in 1943.

Rendered in bold graphics and bright primary colors by the Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller, it depicts a young woman, clad in a work shirt and polka-dot bandanna. Flexing her arm, she declares, “We Can Do It!”

(In 2017, The New Yorker published an updated Rosie, by Abigail Gray Swartz, on its cover of Feb. 6. It depicted a brown-skinned woman, sporting a pink knitted cap like those worn in recent women’s marches, striking a similar pose.)

Mr. Miller’s poster was never meant for public display. It was intended only to deter absenteeism and strikes among Westinghouse employees in wartime.

For decades his poster remained all but forgotten. Then, in the early 1980s, a copy came to light — most likely from the National Archives in Washington. It quickly became a feminist symbol, and the name Rosie the Riveter was applied retrospectively to the woman it portrayed.

This newly anointed Rosie soon came to be considered the platonic form. It became ubiquitous on T-shirts, coffee mugs, posters and other memorabilia.

The image piqued the attention of women who had done wartime work. Several identified themselves as having been its inspiration.

The most plausible claim seemed to be that of Geraldine Doyle, who in 1942 worked briefly as a metal presser in a Michigan plant. Her claim centered in particular on a 1942 newspaper photograph.

Distributed by the Acme photo agency, the photograph showed a young woman, her hair in a polka-dot bandanna, at an industrial lathe. It was published widely in the spring and summer of 1942, though rarely with a caption identifying the woman or the factory.

In 1984, Mrs. Doyle saw a reprint of that photo in Modern Maturity magazine. She thought it resembled her younger self.

Ten years later, she came across the Miller poster, featured on the March 1994 cover of Smithsonian magazine. That image, she thought, resembled the woman at the lathe — and therefore resembled her.

By the end of the 1990s, the news media was identifying Mrs. Doyle as the inspiration for Mr. Miller’s Rosie. There the matter would very likely have rested, had it not been for Dr. Kimble’s curiosity.

It was not Mrs. Doyle’s claim per se that he found suspect: As he emphasized in the Times interview, she had made it in good faith.

What nettled him was the news media’s unquestioning reiteration of that claim. He embarked on a six-year odyssey to identify the woman at the lathe, and to determine whether that image had influenced Mr. Miller’s poster.

In the end, his detective work disclosed that the lathe worker was Naomi Parker Fraley.

The third of eight children of Joseph Parker, a mining engineer, and the former Esther Leis, a homemaker, Naomi Fern Parker was born in Tulsa, Okla., on Aug. 26, 1921. The family moved wherever Mr. Parker’s work took him, living in New York, Missouri, Texas, Washington, Utah and California, where they settled in Alameda, near San Francisco.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the 20-year-old Naomi and her 18-year-old sister, Ada, went to work at the Naval Air Station in Alameda. They were assigned to the machine shop, where their duties included drilling, patching airplane wings and, fittingly, riveting.

It was there that the Acme photographer captured Naomi Parker, her hair tied in a bandanna for safety, at her lathe. She clipped the photo from the newspaper and kept it for decades.

After the war, she worked as a waitress at the Doll House, a restaurant in Palm Springs, Calif., popular with Hollywood stars. She married and had a family.

Years later, Mrs. Fraley encountered the Miller poster. “I did think it looked like me,” she told People, though she did not then connect it with the newspaper photo.

In 2011, Mrs. Fraley and her sister attended a reunion of female war workers at the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, Calif. There, prominently displayed, was a photo of the woman at the lathe — captioned as Geraldine Doyle.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Ms. Fraley told The Oakland Tribune in 2016. “I knew it was actually me in the photo.”

She wrote to the National Park Service, which administers the site. In reply, she received a letter asking for her help in determining “the true identity of the woman in the photograph.”

“As one might imagine,” Dr. Kimble wrote in 2016, Mrs. Fraley “was none too pleased to find that her identity was under dispute.”

As he searched for the woman at the lathe, Dr. Kimble scoured the internet, books, old newspapers and photo archives for a captioned copy of the image.

At last he found a copy from a vintage-photo dealer. It carried the photographer’s original caption, with the date — March 24, 1942 — and the location, Alameda.

Best of all was this line:

“Pretty Naomi Parker looks like she might catch her nose in the turret lathe she is operating.”

Dr. Kimble located Mrs. Fraley and her sister, Ada Wyn Parker Loy, then living together in Cottonwood, Calif. He visited them in 2015, whereupon Mrs. Fraley produced the cherished newspaper photo she had saved all those years.

“There is no question that she is the ‘lathe woman’ in the photograph,” Dr. Kimble said.

An essential question remained: Did that photograph influence Mr. Miller’s poster?

As Dr. Kimble emphasized, the connection is not conclusive: Mr. Miller left no heirs, and his personal papers are silent on the subject. But there is, he said, suggestive circumstantial evidence.

“The timing is pretty good,” he explained. “The poster appears in Westinghouse factories in February 1943. Presumably they’re created weeks, possibly months, ahead of time. So I imagine Miller’s working on it in the summer and fall of 1942.”

As Dr. Kimble also learned, the lathe photo was published in The Pittsburgh Press, in Mr. Miller’s hometown, on July 5, 1942. “So Miller very easily could have seen it,” he said.

Then there is the telltale polka-dot head scarf, and Mrs. Fraley’s resemblance to the Rosie of the poster. “We can rule her in as a good candidate for having inspired the poster,” Dr. Kimble said.

Mrs. Fraley’s first marriage, to Joseph Blankenship, ended in divorce; her second, to John Muhlig, ended with his death in 1971. Her third husband, Charles Fraley, whom she married in 1979, died in 1998.

Her survivors include a son, Joseph Blankenship; four stepsons, Ernest, Daniel, John and Michael Fraley; two stepdaughters, Patricia Hood and Ann Fraley; two sisters, Mrs. Loy and Althea Hill; three grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; and many step-grandchildren and step-great-grandchildren.

Her death was confirmed by her daughter-in-law, Marnie Blankenship.

If Dr. Kimble exercised all due scholarly caution in identifying Mrs. Fraley as the inspiration for “We Can Do It!,” her views on the subject were unequivocal.

Interviewing Mrs. Fraley in 2016, The World-Herald asked her how it felt to be known publicly as Rosie the Riveter.

“Victory!,” she cried. “Victory! Victory!”

more recommended stories

Fentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to Spike, Making San Diego a National Epicenter for Fentanyl Trafficking

Fentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to Spike, Making San Diego a National Epicenter for Fentanyl TraffickingFentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to.

Utah Man Sentenced for Hate Crime Attack of Three Men

Utah Man Sentenced for Hate Crime Attack of Three MenTuesday, August 8, 2023 A.

Green Energy Company Biden Hosted At White House Files For Bankruptcy

Green Energy Company Biden Hosted At White House Files For BankruptcyAug 7 (Reuters) – Electric-vehicle parts.

Former ABC News Reporter Who “Debunked” Pizzagate Pleads Guilty of Possessing Child pδrn

Former ABC News Reporter Who “Debunked” Pizzagate Pleads Guilty of Possessing Child pδrnFriday, July 21, 2023 A former.

Six Harvard Medical School and an Arkansas mortuary Charged With Trafficking In Stolen Human Remains

Six Harvard Medical School and an Arkansas mortuary Charged With Trafficking In Stolen Human RemainsSCRANTON – The United States.

Over 300 People Facing Federal Charges For Crimes Committed During Nationwide Demonstrations

Over 300 People Facing Federal Charges For Crimes Committed During Nationwide DemonstrationsThe Department of Justice announced that.