“There was an internal investigation of the issue conducted by one of my predecessors, Mr. Morell, who found no fault with my actions and that my decisions were consistent with my obligations as an agency officer.”

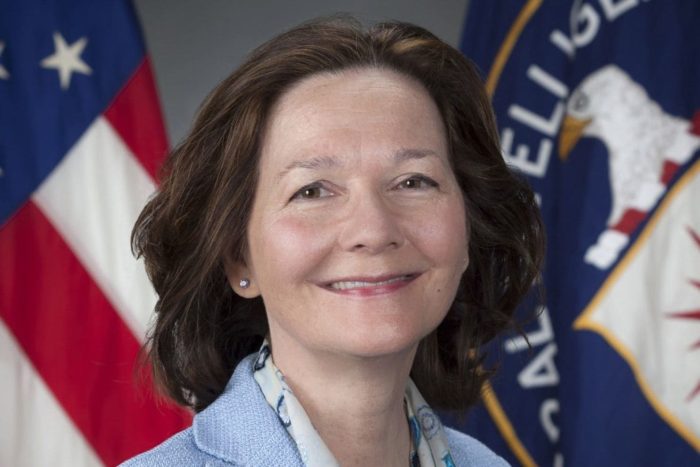

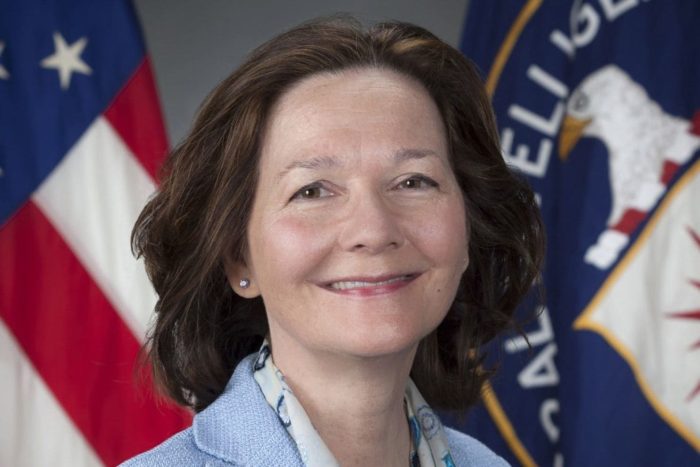

— Gina Haspel, nominee to be CIA director, in remarks during her confirmation hearing, May 9, 2018

A key issue in Gina Haspel’s nomination to be CIA director is her role in the CIA’s 2005 destruction of videotapes documenting interrogation sessions with al-Qaeda detainees using brutal techniques, including waterboarding. In preparation for her hearing, the CIA declassified a 2011 internal disciplinary review, written by then-deputy CIA director Michael Morell, that Haspel and her allies have said exonerated her.

“I have found no fault with the performance of Ms. Haspel,” Morell wrote. He essentially said she was a “good soldier” who followed orders, including an order to draft the cable to destroy the tapes.

But there’s less to this review than meets the eye, and various other accounts (principally memoirs of CIA officials) have raised other questions about her role in the tape decision. During her hearing, Haspel addressed some of those questions. As a reader service, here’s a guide to what happened to the debate.

The Facts

On Nov. 8, 2005, the Senate voted on whether to approve an independent investigation of CIA’s treatment of detainees. The proposal, advanced by then-Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), was voted down, but at the time, a CIA detention facility in Thailand retained 92 videotapes of interrogations — 90 of Zayn al-Abidin Muhammed Hussein (better known as Abu Zubaida) and two of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri. (A 2004 CIA Inspector General report found that 11 were blank, two were mostly blank and two were broken.)

That same day, Jose Rodriguez, then director of the National Clandestine Service, sent a cable to Thailand facility instructing CIA personnel there to use an “industrial strength shredder” to destroy the tapes. On Nov. 9, the tapes were destroyed.

Haspel was Rodriguez’s chief of staff at the time and she testified that she received a notice on her computer that the cable had been sent. In late 2002, Haspel oversaw the secret Thailand facility, where one al-Qaeda suspect had been waterboarded. Another detainee also was waterboarded before Haspel’s arrival.

John Rizzo, then the acting CIA general counsel, had long been involved in the seemingly endless debate inside the agency about whether to destroy the tapes. Rizzo, who has publicly supported Haspel’s nomination, was stunned to learn the tapes had been destroyed because he was under the impression that the issue was once again being prepared for a senior-level decision.

“In truth, I never thought that destruction was a realistic possibility,” he wrote in his memoir, “Company Man.” “There were too many people adamantly opposed to the idea.”

When Rizzo received a message that pursuant to headquarters authorization the tapes had been destroyed, Rizzo sent a one-word email to one of the lawyers on his team who had been working with Rodriguez’s staff: “WHAT?!?!”

In his book, Rizzo says he was not certain what caused the question of tapes to emerge again in November 2005. But an email from Rizzo disclosed by Senate investigators indicates the Levin proposal played a role: “Sen. Levin’s legislative proposal for a 9/11-type outside Commission to be established on detainees seems to be gaining some traction, which obviously would serve to surface the tapes’ existence,” Rizzo wrote to colleagues on Oct. 31. “I think I need to be the skunk at the party again and see if the Director is willing to let us try one more time to get the right people downtown on board with the notion of our destroying the tapes.”

In her confirmation hearing, Haspel insisted the Levin proposal was not a driving factor: “What I recall were the security issues surrounding the tapes. I don’t recall pending legislation.” Rodriguez and Haspel had argued internally that the videotapes showed the faces of the interrogators and if made public could open them up to reprisals.

There was another factor, according to an account Rodriguez recently gave to ProPublica: On Nov. 2, The Washington Post exposed the CIA’s “black sites” for interrogations, including in Thailand, and on Nov. 3, a federal judge in a terrorist trial ordered the government to search for video or audio of captured militants. By Nov. 4, Rodriguez’s office was drafting a cable that led to the destruction of the tapes.

Rizzo’s account, and a memoir by Rodriguez, suggests a more substantial role for Haspel in this matter, though Morell said in his report that he had reviewed both books. Haspel was one of “the staunchest advocates inside the building for destroying the tapes,” someone who “would raise the subject almost every week,” Rizzo noted.

In May 2005, Rizzo wrote, he had raised the question of destroying the tapes again with White House officials and received a very negative reaction. “The message from the White House remained clear: Do not do anything to the tapes before coming back here first.”

When he told Rodriguez and Haspel, he said, “they were crestfallen, because they were now on notice that the DNI [Director of National Intelligence], two successive White House counsels and the vice president’s top lawyer had weighed in strongly against destroying the tapes. To top it off, I confided to them that Porter Goss [then CIA director] seemed distinctly unenthusiastic about the idea too.”

So what happened?

Rodriguez, in his book, “Hard Measures,” said that “to say I was getting frustrated would be a massive understatement.” So, he wrote, Haspel in early November held a meeting with lawyers and asked two questions: 1.) Is the destruction of tapes legal? 2) Did Rodriguez have the authority to make that decision on his own? “The answer she got to both questions was: Yes.”

Rizzo, as he spoke to his “shaken” legal staff to understand what happened, learned about Haspel’s two questions and the lawyers’ response. “Both of their answers were technical accurate, as best I could tell,” he wrote. “But that was beside the point, and Jose had to have known it. He had been on notice by me for three years that the fate of the tapes was not his call.”

Morell, in his book “The Great War of our Time,” noted that a criminal probe led by special prosecutor John Durham decided not to bring charges “as Rodriguez has been told he had the legal authority to destroy the tapes. Durham concluded, however, that such legal authority had not existed and that Agency lawyers had erred in their legal judgment.” (The Durham report has not been declassified.)

Rodriguez dismissed much of the warnings from across the government not to destroy the tapes as opinions, not orders.

The facility in Thailand was sent a cable on Nov. 4 essentially explaining it should ask for the videotapes be destroyed, using “cut-and-paste” legal language provided by Rodriguez’s office. A cable was sent back on Nov. 5, with the exact right language, and Rodriguez asked Haspel to draft the cable “approving the action that we had been trying to accomplish for so long.” He added: “The cable left nothing to chance. It even told them how to get rid of the tapes. They were to use an industrial-strength shredder to do the deed.”

Once Haspel completed the cable, Rodriguez studied it for a while: “I took a deep breath of weary satisfaction and hit Send.”

Rodriguez claims that Rizzo’s office was sent a copy of the draft cable telling the Thai facility to ask for permission. But in Rizzo’s account, Haspel and Rodriguez had misled his office. His lawyers told him “there was language in it that bore no resemblance to what they had been working on with Jose’s staff.”

A Nov. 10 email released by the CIA, from an unnamed official to then-CIA Executive Director Kyle “Dusty” Foggo, said: “I am no longer feeling comfortable” with the decision now that he had learned Rodriguez had not cleared the decision with Rizzo or the CIA’s inspector general. White House counsel Harriet Miers was said to be “livid” about the action after Rizzo informed her. Haspel’s name is redacted in the email, but it refers to her time spent overseeing the interrogation facility in Thailand.

“Cable was apparently drafted by [redacted] and released by Jose; they are only two names on it so I am told by Rizzo,” the email said. “Either [redacted] lied to Jose about ‘clearing’ with [redacted] and IG (my bet) or Jose misstated the facts. (It is not without relevance that [redacted] figured prominently in the tapes, as [redacted] was in charge of [redacted] at the time and clearly would want the tapes destroyed.)”

“In my thirty-four year career at CIA, I never felt as upset and betrayed as I did that morning,” Rizzo wrote.

In her testimony, Haspel repeatedly insisted that Rodriguez decided on his own to destroy the tapes and she was under impression he would first clear it with the CIA director.

“He took the decision himself and he said it was based on his own authority,” she testified. “I asked him if he had had the consultation with the director at the time as planned, and he said he decided to take the decision on his own authority.”

When asked whether she understood why the cable was sent without alerting lawyers in the general counsel’s office, she replied: “Mr. Rodriguez chose not to copy the lawyers on the cable because he took the decision on his own authority and he wanted to take responsibility for it.”

Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) noted that the Morell report said: “The record is clear that Mr. Rodriguez was aware that two White House Counsels, the counsel to the Vice President, the DNI, the DCIA, and the HPSCI [House Intelligence Committee] ranking member had either expressed opposition to or reservations about the destruction of the tapes.” In fact, this fact is what swayed Morell to conclude Rodriguez should receive a disciplinary letter.

King asked whether Haspel also knew this at the time. “I don’t believe I knew that entire list, but I knew there were some objections and that is why we were going back to the director of the Central Intelligence Agency,” she replied.

Interestingly, Rodriguez in his memoir does not indicate at all he had such a misunderstanding with his chief of staff. Indeed, in an interview with ProPublica published on May 9, he said he told her he would take matters into his own hands. He told her the agency was just going to kick the can down the road and together, he said, they worked out a plan to finally resolve the problem, which included asking the lawyers whether Rodriguez could order the destruction of the tapes.

“She was concerned that I was taking this risk on my own — that I was putting myself in this situation,” Rodriguez recalled to ProPublica. “She didn’t say, ‘Don’t do it.’ She may have thought I was going to talk to more people about it before hitting ‘send,’ but I had made up my mind that I was going to follow through.”

The Pinocchio Test

This situation does not easily lend itself to Pinocchios, given the contradictory recollections. But the Morell review does not resolve those contradictions. Haspel clearly was heavily involved with the effort to destroy the tapes, such as asking week after week about the issue, getting the legal guidance sought by Rodriguez and drafting the actual cable ordering the destruction of the tapes.

Haspel insists that she thought Rodriguez would not act before discussing the matter with CIA Director Goss. If so, it’s unclear why a draft cable ordering the tapes destroyed was necessary in order for Rodriguez to discuss the issue with Goss. Moreover, why would Haspel need to ask lawyers if Rodriguez had the legal authority to destroy the tapes if he had intended to ask Goss for permission?

Readers can judge for themselves whether Haspel should have realized that Rodriguez would not meet with Goss before giving the order, given the steps she and her boss had already taken before he pushed the send button on the cable she had written.

more recommended stories

Fentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to Spike, Making San Diego a National Epicenter for Fentanyl Trafficking

Fentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to Spike, Making San Diego a National Epicenter for Fentanyl TraffickingFentanyl Seizures at Border Continue to.

Utah Man Sentenced for Hate Crime Attack of Three Men

Utah Man Sentenced for Hate Crime Attack of Three MenTuesday, August 8, 2023 A.

Green Energy Company Biden Hosted At White House Files For Bankruptcy

Green Energy Company Biden Hosted At White House Files For BankruptcyAug 7 (Reuters) – Electric-vehicle parts.

Former ABC News Reporter Who “Debunked” Pizzagate Pleads Guilty of Possessing Child pδrn

Former ABC News Reporter Who “Debunked” Pizzagate Pleads Guilty of Possessing Child pδrnFriday, July 21, 2023 A former.

Six Harvard Medical School and an Arkansas mortuary Charged With Trafficking In Stolen Human Remains

Six Harvard Medical School and an Arkansas mortuary Charged With Trafficking In Stolen Human RemainsSCRANTON – The United States.

Over 300 People Facing Federal Charges For Crimes Committed During Nationwide Demonstrations

Over 300 People Facing Federal Charges For Crimes Committed During Nationwide DemonstrationsThe Department of Justice announced that.